Nowadays, it’s possible to travel chiefly for recreation. Longer ago, however, travel had additional importance. The journals and observations of travelers of years past constitute an important, and sometimes unique source of information about a country’s historical situation. You will find ample evidence of this even in the first few pages of “Foreign Travelers in Greece, from A.D. 333 to A.D. 1821,” by Kyriakos Simopoulos. The detailed and often remarkable descriptions left by travelers over the years are surprising. In this worthy volume, you will encounter many stories about pirates, sea battles, treasure hunting, and unexpected twists of fate.

Many is the traveler who, Pausanias in hand, set out in search of the mysteries of Ancient Greece. They would arrive at the famed Delphi only to find that the stadium had been transformed into a corral, and the inscribed tablets of oracular revelation incorporated into the huts of the local villagers. By all accounts, a similar situation existed throughout Greece. Some Philhellenes recognized the beauties of antiquity amongst the ruins, the faces, and the customs of the locals. Others, possessed with a mania for treasure-hunting, toured Greece especially from 1770 to 1820, and loaded their homebound ships with priceless antiquities.

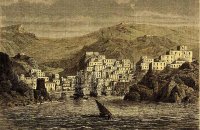

“Tuesday, 12 August, the Ambassador (Count of Marcheville) rented a caique and we went to Delos, ten miles west from Mykonos. We saw the remnant of an ancient temple, and the great statue of its god dismembered. . .here a torso, there a bit of thigh. The rest had been taken by the curious who visit the island every so often. I am among the guilty, as I chipped off a chunk and took it along as a souvenir.”

Particularly after 1600, the accounts become richer, more detailed, and often include personal opinions and comments.

You will read of the visitor’s indelible impression of the elegant and noble women of Chios; the local garb of Milos—ladies’ skirts cut short for the season; the customs and the dances of the Aegean islanders; the superb climate which ensures good health. (The last seems to account for the absence of doctors in most places).

“Chios is the most agreeable place in the Turkish Empire, thanks to its mild climate, the fertility of its land, and the affability of its residents. . .the ladies are very beautiful (you’d be hard pressed to find an ugly one amongst them). . .they go to and from as they please. They seem to have a special affinity for foreigners. They are gorgeous. They play musical instruments, they sing, they dance wonderfully.”

Even the most everyday moments of life do not escape the eye of the travelers, who manage to describe weddings, childbirth, death and burial customs, exorcisms, work, and really whatever else attracted their attention.

The Symiote sponge-diver explained, in a sort of Western tongue, that sponges grow on the rocks ten, maybe twenty fathoms below the surface of the water. “They soak half of a sponge in oil, the other half in an astringent so that it won’t absorb the oil. Then they put it in their mouth, leaving the oil-soaked part outward. They bite down on it, hard, and that way the sponge prevents water from entering their mouths. then, they dive into the sea. there in the depths, by sucking on the sponge, they can extend the length of their dive under the water. . .”

Among the journals and letters of these travelers, manners and customs of many parts of Greece have been transmitted: contemporary medical knowledge, superstitious beliefs, descriptions of torture, etc. Run of the mill for daily life of the period. Frequently, the role of the clergy and the Church is mentioned. Certainly, there is no shortage of pithy observations about Greek idiosyncrasies, particularly from traveler to traveler.

At the foot of the monastery on Patmos, the French traveler Choiseul-Gouffier writes of his encounter with a learned man of the cloth: “A monk who had come hurriedly down the hill asked me, in Italian, where I was from and what had happened in Europe these last seven years. When he learned I was a Frenchman, he exclaimed, “Voltaire lives?!” Imagine my surprise.”

This traveler later served as ambassador at Constantinople, and had as a companion in his hunt for antiquities the painter Fauvel, guilty of immeasurable pillage and destruction all across Greece.

The French traveler Savary spent eight weeks on Kasos. During his stay, a Kasiote barge arrived, loaded with rice, melons, pomegranates, and other fruits.

“All the women went down to the seaside. They ran hurriedly to welcome their brother, their father. I had never seen such a warm display of tenderness. They hugged each other tight, and blessed the Lord for their safe return. There are the ancient Greeks, I said to myself; there the vivid imagination always ready to catch fire. There, the exquisite sensitivity that distinguishes them from all the other peoples of the earth. This rock protects them from the Turkish yoke, and allows them to preserve their ancient character.”

The importance of information passed down by these travelers remains significant even today. Moreover, the transmission of travelers’ personal experience is irreplaceable, as it adds so many shades of meaning and different points of view. Business amongst pleasure, then. Don’t be shy to keep your own travel diary, which may prove invaluable to your traveling contemporaries, maybe even to the scholars of the future.